Content structure work is getting a lot more mainstream attention these days, and for good reason. [People have been creating structured content since long before there were computers, but there has definitely been a decent, if somewhat niche, focus on structured content throughout the computer era. But for many reasons, the internet era didn’t always have a broad focus on structured content, and many businesses, designers, and developers “grew up” in the internet for years without realizing the potential of structured content to supercharge their work. A rant for another day.] Structured content can make it easier to measure and achieve business goals, and it can make it much easier to fulfill the needs of your audience.

Unstructured content

What do we mean when we say structured content, first of all? It may help to understand what unstructured content is. When you read a website or use an app, you can’t tell what the content looks like on the back end, where writers and editors input the content to the software that runs the site. Once we started creating software — often a content management system or a CMS — to help writers update websites, we created forms for them to use to add the information. For a long time, the forms looked like this:

In fact, many of the forms still look like that.

Even in the beginning, this kind of form didn’t work. In the beginning of the internet, many of the writers working on the web came from print. We were used to writing something in a Word document, and either formatting it there, or importing the words into a desktop-publishing program that allowed us to control format, so we had total control over what parts of the work caught the reader’s eye first, or what seemed most important, or what was a quick takeaway, or what color and how big the letters of our headline were over the background image.

So we wanted parity in the online world. We demanded, and got, WYSIWYG editors for our digital work. [Those are the what-you-see-is-what-you-get formatting tools like the B, I, U, alignment, and other formatting tools available in Word, many other programs, and also on the back end of many websites.] And for a while, many editors were happy with that.

Those of us who came from a more tech-centric viewpoint, or who were tech-curious, and kept worming our way into programming meetings and hitting up our developer friends to teach us some Java on the side, realized that there were more options. The problem with the body field has been well defined by now, but this problem is not necessarily common knowledge outside the content strategy and programming worlds—in the business world. To help you see the problem, and to see the opportunities available from structure, let’s start with some examples.

Structured content examples

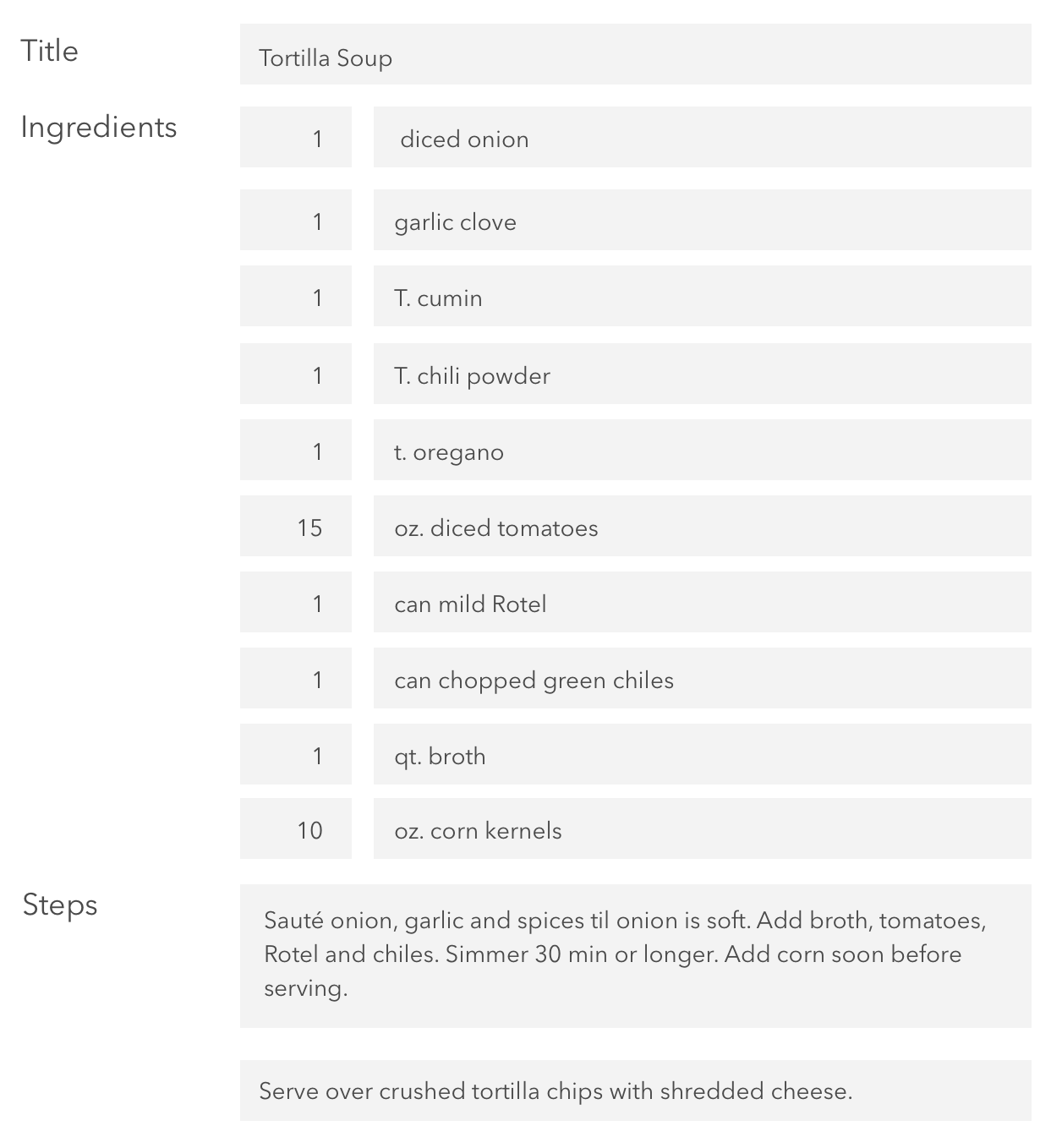

A quick example of structured content that everyone understands: Recipes. Recipes typically come with information in several parts: The title, the ingredients and their amounts, the step-by-step instructions. You might have additional information like nutritional data, servings, recipe author or source, images, and categories like breakfast or vegetarian.

A movie listing is another great example. Movies have a title, a description, a cast list, a theater, a start time, a producer, and on and on.

Now, it’s not just that recipes and movies have these parts that make them structured. We could take all of that information and slap it into a body field.

We’d need to add some code to the recipe so that it would show up in an understandable way online, but we could do that.

And even so, it’s still not structured — because the computer doesn’t understand what the information is yet. The computer just knows: Here are some bold words. Here is a headline. Here are some italic words. Here are some more words. Here is a line break. And it will render them as such, and to the user, the cook making the soup, everything looks fine.

Structured content

What happens if the cook is expecting guests for dinner and wants to increase the soup by 50%? If the content isn’t structured, the cook has to do the math and hopefully remembers how to multiply fractions. But if the content is structured, the cook may be able to enter a number of servings she’d like to make in the recipe app and have the recipe instantly update to give her new amounts for each ingredient. To make that happen, we need a lot more than a body field on the back end. We need something more like this:

Then the recipe app can perform all kinds of operations on its information, because it understands that some of those fields in the soup recipe are numbers. It can also update nutritional information when data changes, and all kinds of other things, if you design it to do so.

Going beyond the obvious (and into your business)

Creating recipe apps that calculate ingredients based on the number of servings needed is an excellent use of structured content. But if your content doesn’t appear to have a natural structure like a recipe, you might be thinking none of this applies to you.

Structured content can do more than allow you to operate on the numbers buried in your raw data, though. Structured content:

- Decreases repetition—Increasing accuracy, reducing the possibility of human error, and improving efficiency

- Provides helpful focus and a predictable, professional experience for consumers/readers/end users of the content

- Optimizes operations by helping content creators focus on the essential

- Makes your content easier for search engines [on your own site and the big ones like Google and Bing] to analyze and use

When I help companies create structured content, I’m often helping them find those less-obvious examples of structure, and they may have many different goals in mind. Here are some common goals for structured content work:

- Make it easier to find relevant information quickly

- Reduce duplicate content

- Reduce the time it takes to create and update content

- Make my content available in many different forms, in a way that works in all those different channels

- Categorize content effectively for users

- Make it easier to analyze what content my audience wants and what content is effective

Those are just a few — there are many more reasons to structure your content.

Two kinds of content structure: Internal and external

I also think about different types of structure that relate to content. Some of the structure is internal to the content itself—a single recipe includes a title, ingredients, and instructions, so those are all part of the recipe. Each of those elements is a bit of internal structure—and we can’t have the recipe without all its ingredients, or steps, or its name.

On the other hand, once we have a recipe, we might categorize it by the meal when we most often eat that dish, or we might tag the recipe by the occasion when it is served. I think of that as external structure—It would still be a good recipe for coconut cake if we didn’t know you recommended serving it for dessert or at Christmas, but that external structure adds to our understanding and gives us greater context.

When you think about your organization’s content, you may have internal or external structure opportunities, or both. Most business people that I talk to initially only think about the external structure, asking questions like:

- Where should this go in the navigation?

- What other content is like this?

- What products is it related to?

All of these are good questions, and they can help us build navigation, and tagging, and taxonomies of information that make content more useful. But they don’t get at the internal structure of content.

Creating internal structure for text-based content

Many times, we miss opportunities for internal structure in text-based content. For instance, think about a software product description. Software products might not have dimensions or a number of pages like a physical product, but they do have features. What if we described those features in bullet form — short phrases? That would be helpful to the user. We could separate those features into individual fields, and then we can re-use each feature somewhere else on the site — perhaps in a comparison chart. If we remove a feature, or update it, we can update that information in one place in our CMS, and it will update the product description page and the feature comparison chart.

If we have a lot of press releases on our site, we probably identify a media contact and their contact information on each one. If our media contact gets promoted and now we have a new person we’d like the press to call, we might have to update hundreds of old press releases — if we had put the media contact information in the body field on each press release. But if we made “media contact” its own type of content, and just referenced that on the press release template, then when Katie gets promoted and Sam takes over media contact duties, we swap her name and info with his in one place, and the system updates it everywhere automagically. That’s the power of structured content, in a very simple demonstration.

Better customer information through structured content

One of my favorite secrets about structured content is this: When you use structure to create content, often your customers have a better experience. I like to create an outline of any type of content before I begin, thinking about my business goals, the audience goals, and how I can best match the two. I consider my message, how I can most effectively convey that to the audience, and how I can demonstrate to them clearly and quickly that I understand and identify with their needs. Once I know all of that, then I’m ready to create content. Often, the back end is more complex than a body field — sometimes to create semantic meaning in a way that helps machines understand and use the content, and sometimes in a way designed to ensure that I create the right content for my audience, even if the end result looks as if it could have been built in a body field.

The rise of data-focused applications

Most people engaged in ecommerce, supporting a database of products, realized a long time ago that they needed to store their product information in a standardized way. [To be honest, most of the structure around products probably started for inventory and bookkeeping purposes, but marketers figured out how to make use of that data.]

As digital applications have developed agility over the past few years, and smartphones have everyone’s customer demanding instant answers at their fingertips, many organizations have realized that organizing their information in a structured way makes it more dynamic, even if they aren’t selling products from a database.

If you’d like to understand how to create content for chatbots or smart speakers, you’re going to need to get into structured content, as well.

The skillsets you need for structured content

If you are ready to consider how structured content could help you meet your business goals, or better serve your audience, you’re not alone. But you may need new skillsets on your team to achieve these goals. At a minimum, you need a structure-oriented content strategist on your team. Content strategists come in different flavors. Some focus more on messaging, business goals, and editorial calendars—and they are often involved in content marketing, or UX/product content writing. For structured content, you want a strategist who understands information architecture for users and for backend design—the one who works with database analysts and UX designers on product development. That might be the same person who can plan and create great lead-generation content for you, but it might not.

Once you’ve designed your content structure, any good writer can use that structure to meet your business and audience goals, but it makes sense to evaluate your structure from time to time to consider new opportunities, as well.